Space of Flows: Framing an Unseen Reality

Curator: Iris Sikking

CURATOR’S STATEMENT

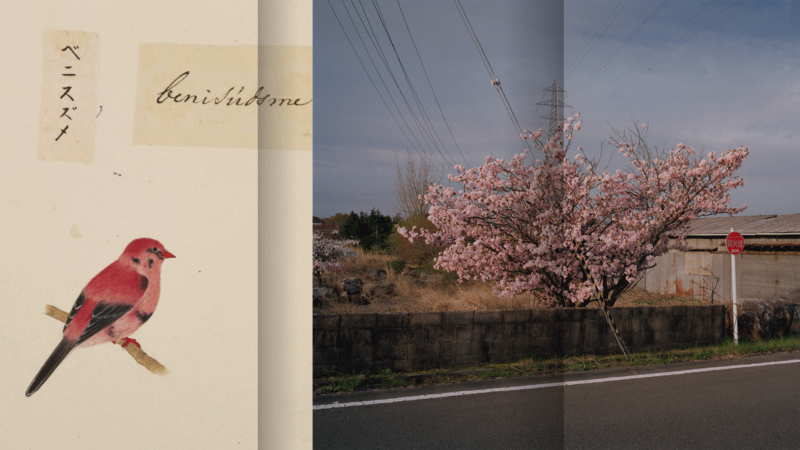

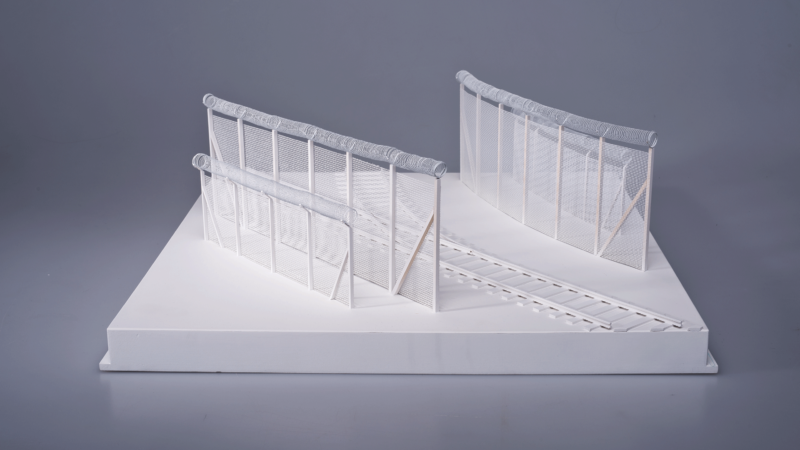

Featuring an international slate of artists, the festival focuses on the ceaseless flow of people, information, and substances, through expanding urban areas, the virtual realm of cyberspace, and endangered natural landscapes. In the face of worldwide streams of refugees and migrants, an overload of manipulable digital information, and injurious amounts of harmful particles suspended in the atmosphere and discharged into waterways, those in power look the other way. And all the while they withdraw and intensify control to protect what they have. Short-term success is favoured over having a sustained vision of the future.

The programme derives its thematic approach from the concept of the “space of flows”, as set forth by the Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells in his seminal 1996 volume The Rise of the Network Society. “The space of flows”, explained Castells, “dissolves time by disordering the sequence of events and making them simultaneous, thus installing society in eternal ephemerality”. Two decades later, one could say that we exist in exactly such a society: a networked one, defined as an open, borderless, and intangible entity, in constant flux and an ever shifting shape. It is our shared experience that we are all part of an enmeshed whole that provokes and confronts us on a near-daily basis with events unfolding in faraway locales. As we take note of them via our screens in the form of a tweet, an image, or a video they evade traditional geographic boundaries and notions of localness. And the speed with which people, goods, information, and pollutants are distributed and disseminated is so rapid that it is sometimes impossible to distinguish between catalyst and consequence. Moreover, how should we judge a message on our screen? Can we really see and understand what is going on?

“Because networks do not stop at the border of the nation-state, the network society constituted

itself as a global system, ushering in the new form of globalisation characteristic of our time.

However, while everything and everybody on the planet felt the effects of this new social

structure, global networks included some people and territories while excluding others, so

inducing a geography of social, economic, and technological inequality.”

Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society

Through the rise of the network society, a real virtuality became visible, making us aware that we are no longer only living in a “space of places”. Castells explains this as a space in which we were familiar with every nook and cranny of our village and acquainted with all our neighbours, and in which we could trace in our minds the jigsaw configurations of the horizon-bound fields. A new layer was created, and this “space of flows” catapulted us into a fluid ecosystem that requires a substantial shift in our perspective on humanity and the planet. On that note, Rebecca Solnit, author of River of Shadows, describes the ascents of Hollywood and, somewhat later, Silicon Valley as those of industries which have reshaped “a world of places and materials [into] a world of representations and information, a world of vastly greater reach and less solid grounding”. And it is precisely the industries of Hollywood and Silicon Valley that by and large define the frames through which we perceive and see the world.Solnit interweaves her biography of Eadweard Muybridge, the photographer and innovator of early motion-picture studies and technologies, with meditations on the concept of “the annihilation of time and space”. “The annihilation of time and space” is an expression from the Industrial Revolution used to describe the groundbreaking, time-altering technologies of the day, such as rail travel and the telegraph, both of which aimed to accelerate lines of transportation and communication.In this respect, each new technology functions as yet another medium that enhances our experience of time and space. But do they bring us a clearer vision? Or do they blur our minds instead?

The artists selected for this year’s Photomonth present projects that encourage us to develop ways of thinking that refuse to be hemmed in by boundaries and led by prejudices. The works provoke a more informed, flexible, and empathetic response to the most pressing issues that we, as humans, face today. As such, the festival focuses on the tension between the impulse to delimit a space with walls and to fearfully exclude the unknown, and the impossibility to regulate processes of moving enormous quantities of people, information, and substances within and across physical and virtual spaces. Envisioned as one overarching group show, the festival blends stories and images in an attempt to examine the “space of flows” that we currently inhabit, and grapple with its implications.

To distinguish between the myriad focuses of the artists’ projects, they have been divided into three chapters: migration to and within contemporary Europe; the invisibility and intangibility of digital data; and urgent environmental issues. The exhibited works address multiple topics, including: societal anxieties stirred by ignorance and mistrust, as well as political fearmongering; consequences of human interventions for the climate; stories of forced displacement; and the growing threat of cyberwarfare.

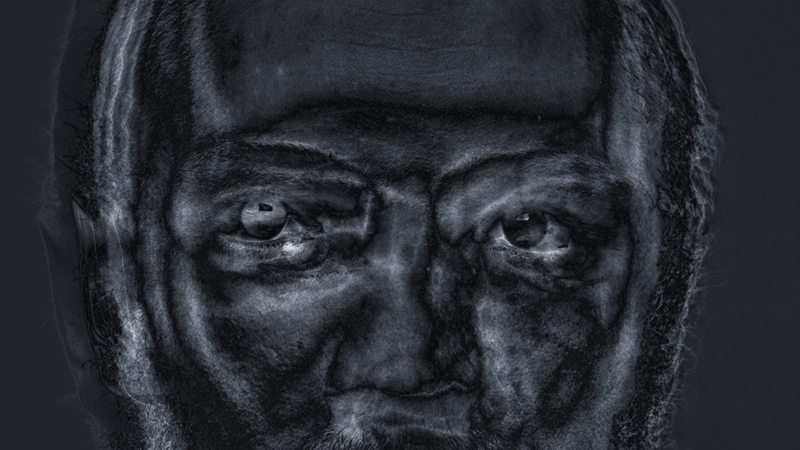

Conflicts, unemployment and lack of prospects have forced untold thousands of people to leave behind their homes, belongings, and loved ones. Refugee or migrant, they undertake an often perilous journey to promised lands where they find themselves at risk of being detained and targeted by the rhetoric of populist political movements.Europe finds itself divided between the liberal values of tolerance and the nostalgia of those who crave a return to a fantasised past in which “everything was known”.

Meanwhile, in an etheric elsewhere, our data hover invisibly in an artificial “cloud”, or else whizz in the blink of an eye through cables snaking underground and undersea. In truth, the vast majority of us don’t have a clue what happens to our data after their transformation into bits and cascading scrolls of zeroes and ones. Computer programmers, cryptocurrency experts, and bitcoin speculators have little interest in making their shadowy realm more transparent or comprehensible to the layperson. The rest of us are left in the dark as to what exactly happens to the digitised facsimiles of ourselves, once rendered and uploaded. What subcutaneous layer, for example, do we unwittingly expose when we pass through an airport’s body scanner?

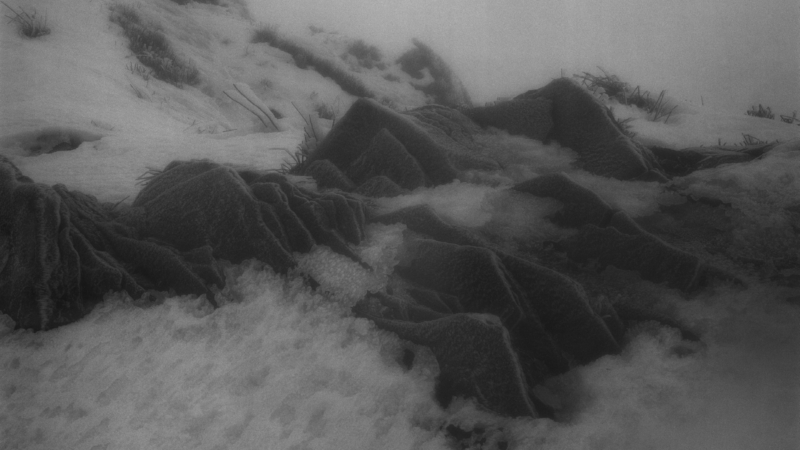

And although “wild nature” has been reduced in many latitudes to a contradiction in terms, it is still a quality we seek out and yearn to experience. In some regions of the world in which a highly cultivated natural environment is mistaken for its original state, we have been disrupting natural processes for ages. Heavy industries such as mining, the presence of nuclear power plants, and what goes under the name of forest management have had a profound, and in many cases irreversibly deleterious effect on the well-being, and long-term vitality of both human and animal habitats.

Even if statistically calculable, it remains difficult, if not impossible, to visualise and truly comprehend the vast movement of migrant populations, the frictionless transfer of encoded data and its ciphered binary digits, and the large-scale release of contaminants into our air, soils, and water. Nevertheless, all the selected artists attempt to do just that: with their lens-based art, they make the “space of flows” more fathomable by humanising its statistics, personalising and particularising its abstractions, and demystifying its technophilic enigmas. Their art stimulates and resonates with the intellect, imagination, and conscience of the viewer.

Iris Sikking (1968) is an independent curator, educated as a film editor and a photo historian. As a curator and author, she positions herself in the overlapping fields of photography and video art with a focus on a cinematic approach and creating narrative structures.

For 10 years now she has conceived exhibitions in the Netherlands and abroad, including, for Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam, Baby: Picturing the Ideal Human, 1840–Now (2008); Dana Lixenberg’s project The Last Days of Shishmaref (2008); Geert van Kesteren’s exhibition Baghdad Calling (2008); and thematic group exhibit ANGRY: Young and Radical (2011). She additionally served as producer and curator for Poppy: Trails of Afghan Heroin (2012–2016), a four-channel installation by Robert Knoth and Antoinette de Jong which was presented worldwide; as curator of Yann Mingard’s Deposit (2015) for Fotomuseum Antwerp; and as guest curator of a group show for Kraków Photomonth 2016 entitled A New Display: Visual Storytelling at a Crossroads.

In addition to her curatorial projects, she carries out portfolio reviews, serves on multiple competition juries, and was recently appointed to the advisory committees of the Mondriaan Fund and Stroom Den Haag. She is also a tutor at the Academy of Art and Design St. Joost (Breda, NL).

The visual artists taking part in this edition of Photomonth are unique in their ability to unravel the present, while simultaneously accounting for the past and imagining possible futures. In the heavily charged image culture of our contemporary societies, we are in need of artists who are able to frame complex realities in ways that push us out of our comfort zones, and that motivate us to reflect upon our own deep-seated and perhaps unacknowledged anxieties and attitudes toward the unknown, the unseen, and the overlooked, in our own geographical or virtual backyard. The frame and focus that the visual artists offer on this “unseen reality” works as an interlude, and distinguishes a fragment of its pristine or proposed reality.

In conceiving their projects, the artists relate to a practice which Alfredo Cramerotti, within the context of a fractured mediascape and the waning influence of “reliable” news outlets, has defined as “aesthetic journalism”. “The relationship between journalism and art is a difficult territory to chart”, he writes, “What I call aesthetic journalism involves artistic practices in the form of investigation of social, cultural, or political circumstances. Its research outcomes take shape in the art context, rather than through media channels”. Many of this year’s Photomonth artists have collaborated or consulted with scientists, journalists, and specialists in order to obtain deeper insight into their subject matter.

Well aware of the fact that an image, as Fred Ritchin observes in his unprecedented book After Photography, “is no longer a tangible object, a rectangle resembling a painting”, but rather “a part of a larger array of linked dynamic media”, the artists have sought to explore new formats for presenting their findings at the festival. Thus, in addition to photographic prints, video installations, and publications, they also include sound and sculpture in the spatial design of their exhibitions, supplement their findings via the incorporation of found footage and materials culled from archives, and make use of modern technological devices to compose their images.

Exhibitions, both solo and collective, are presented at ten locations in the city of Kraków.